This blog started life as a Twitter thread, written as we watched the Parliamentary ‘debate’ on 8 March about breastfeeding support. Read and weep for women’s rights, autonomy and evidence-based healthcare policy!

On International Women’s Day 2022, some Parliamentarians met in Westminster to ‘debate’ breastfeeding support. The debate was informed, in part, by a survey of parents’ views led by Alison Thewliss MP. We were concerned by the biased nature of the survey questions, as well as by the fact that we had only seen the survey shared by breastfeeding advocacy groups. However, Thewliss reassured Sue Haddon that she sought ‘balance’ in debate. You can watch the ‘debate’ here from 16:23.

Thewliss started by sending her best wishes to ‘those who are very proud of meeting their breastfeeding goals’ and her love to ‘those who have struggled…and carry those feelings around for the rest of their lives’. We have a problem with this dichotomy. Breastfeeding is feeding a baby, not a performance to be proud of. There are no gold stars or glitter boobies. And as for framing those who struggled as carrying around ‘difficult feelings’ for the rest of our lives. That just reeks of the institutional narcissism, gaslighting and twisting of women’s stories that Ruth Ann Harpur blogged about recently. We don’t want your love and we don’t need emotional support, Alison Thewliss. We want safe and evidence-based infant feeding policy that ensures babies are safely fed!

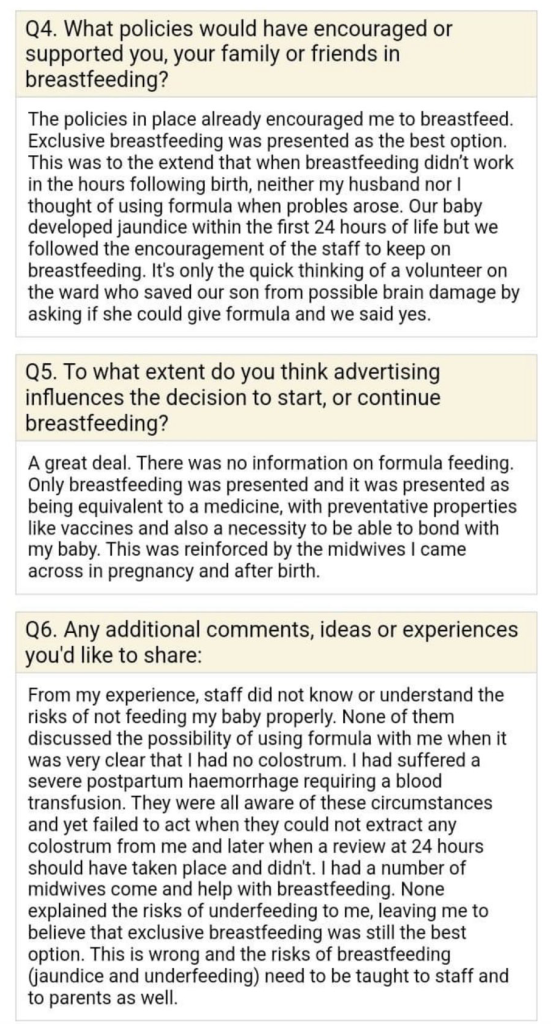

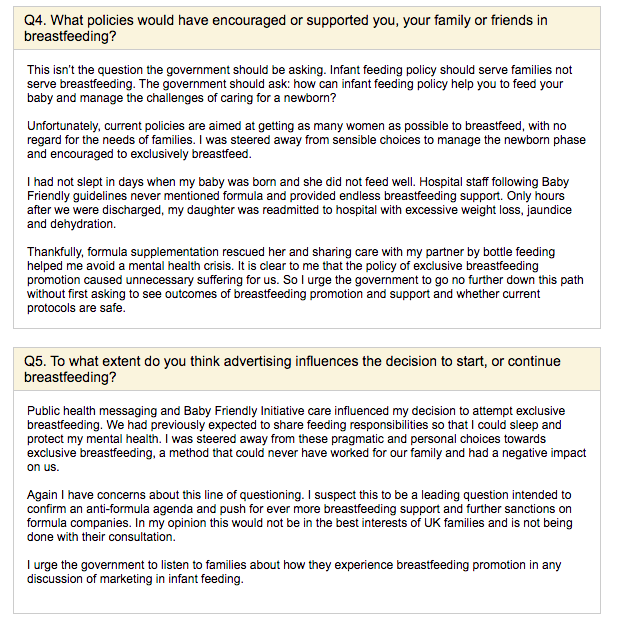

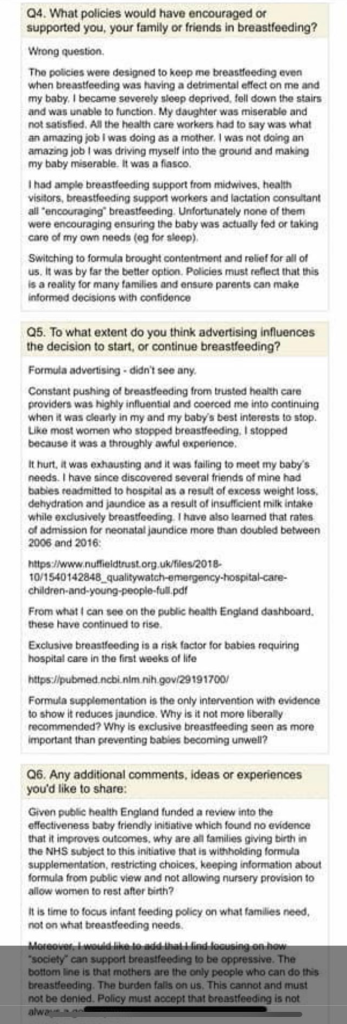

Unfortunately, history has taught us that we cannot expect our stories to be heard with open hearts, open minds and a willingness to learn what parents want and need from infant feeding policy and practice. We can’t trust Alison Thewliss to tell our stories. So we saved them. Here’s a sample of the stories you won’t be hearing in the debate, because they are examples of direct harms caused to babies and mothers as a result of current breastfeeding promotion policies:

Thewliss goes on to report proudly on the success of Scotland’s breastfeeding promotion initiatives and the number of babies breastfed for at least some time in Scotland. She doesn’t present a shred of evidence that the health of Scotland’s babies has improved as a result. She refers to the £50 million the government has already committed to breastfeeding support and wants more detail on how that is to be spent. So do we! Because, guess what? The recent NICE review of the evidence on breastfeeding support failed to identity any evidence for what was effective at helping people to breastfeed.

Thewliss says she hopes she is able to address all the concerns raised in her survey, although ours are conveniently missed. She cites parents as wanting better information about breastfeeding, feeding support, lactation consultants, tongue-tie surgery and breastfeeding education in schools (from breastfeeding advocacy groups? No, thank you!) She is very concerned about formula marketing, but she wants more government advertising for breastfeeding, including giant murals of breastfeeding mermaids in order to normalise breastfeeding. OK…

The most recent national Infant Feeding Survey found women stop breastfeeding because of issues with pain, latching and low milk supply. Thewliss doesn’t note the lack of evidence-based interventions for these problems. However, she does note that provision of tongue-tie treatment, which she states can ‘make all the difference’ with breastfeeding, is patchy. The evidence for tongue-tie surgery is also patchy! There is a burgeoning private market selling it to desperate parents seeking solutions to intractable breastfeeding problems. Are Alison Thewliss’s concerns about exploitation of ‘parents’ wish to do the best for their babies’ limited to formula companies? Or do they extend to the unethical marketing of tongue-tie surgery, with parents paying for surgery they have been misled into thinking is effective when the evidence is sparse?

Likewise Thewliss advocates for more lactation consultants. Again, she doesn’t seem to be aware that the NICE review of the evidence did not find any evidence to say what would help prevent or resolve common breastfeeding problems. Families need evidence-based information and care!

Thewliss refers to Professor Amy Brown and Dr Natalie Shenker’s research into the impact milk banks can have on maternal mental health, providing reassurance for mums until their own milk comes through. Erm… we aren’t aware of any evidence that donor milk improves mental health outcomes. And moreover, mothers could be equally reassured that their babies’ nutritional needs were met by formula until their milk comes in, if breastfeeding advocacy hadn’t caused so much fear of formula in the first place! There is not a single study showing benefits of donor milk over formula for healthy term babies. Last we checked, donor milk costs about £7.50 for 50ml (in addition to the personal costs to donors – time, energy and effort in expressing milk); ready-to-feed formula costs 16p for 50ml.

Then Labour MP Fleur Anderson takes the floor. She highlights the lack of services during and after the Covid-19 pandemic, including baby weighing clinics. We think this is a concern because of the potential for health issues to be missed! Babies weight and health checks should be the priority, not breastfeeding! She says that breastfeeding and maternal mental health are intertwined and that breastfeeding can strengthen resilience. There’s no evidence that increasing breastfeeding improves mental health outcomes, but there is evidence that current breastfeeding policy may lead to adverse psychological outcomes.

Anderson calls for the restoration of NHS services annihilated by the pandemic. We agree, but let’s make sure those services are using evidence-based practice and focused on meeting the needs of families, not on pushing more breastfeeding. She also calls for peer support services with training, supervision and an IBCLC clinic for ‘complex cases’. There is still no evidence for what interventions prevent or resolve common breastfeeding problems. And, by the way, Anderson doesn’t look at what happened to breastfeeding rates when publicly funded breastfeeding support services weren’t available in her constituency. If South West London is like the rest of the country, rates went up! So, with less investment and apparently almost total annihilation of professional breastfeeding support services within healthcare, there was more breastfeeding! What is this £50 million being used for exactly?

We won’t cover all contributions because time is limited. In any case, all MPs participating in the ‘debate’ were passionately convinced that breastfeeding is the best start for babies. Unfortunately, we shouldn’t mistake passion for breastfeeding as passion for meeting the needs of new parents, as they feed their babies.

The Millennium Cohort study is referenced as demonstrating that breastfeeding improves outcomes for children, but this study is a correlation-based population study that cannot adequately control for confounding variables. We repeat: there remains no study demonstrating improved health or educational achievement as a result of breastfeeding promotion and support initiatives in the UK (or a comparable high-income setting). This confidence is grossly misplaced.

It is also worth noting that throughout the debate there is a lot of emphasis on breastfeeding as normal and natural. Has Parliament learned nothing from the normal birth agenda and the impact on patient safety of emphasising what is ‘natural’?

Towards the end of the ‘debate’, Maria Caulfield, Minister for Patient Safety, replies to the questions and demands made. Does she challenge any of them? No. She claims that breastfeeding reduces infections, breast cancer, childhood and maternal obesity, and improves parent-child emotional wellbeing and attachment!

Woah! The evidence on infection is debatable. Some studies (notably conducted in Belarus in 1990) show modest benefit, but the applicability to the UK in 2022 is not known. The only study comparing breastfeeding support to standard of care found breastfeeding support increased obesity rates! There is no good evidence that breastfeeding improves emotional wellbeing and parent-child attachment. (Ruth Ann Harpur, our resident clinical psychologist and relationships expert rolls her eyes and says anyone who claims this doesn’t understand relationships or attachment!)

If Caulfield wants to be mindful of those for whom breastfeeding doesn’t work out, we suggest starting with a more sensible assessment of the health effects of infant feeding methods and acknowledgment that exclusive breastfeeding, carries risks. These include the risk of jaundice, dehydration and hypoglycaemia as a result of insufficient milk intake, which some of us in IFA experienced with our babies. Will the Minister for Patient Safety take this into consideration as she looks at infant feeding policies? As parents, we don’t want ‘support and reassurance’. We want safe infant feeding practice that prioritises preventing readmission of babies for jaundice and other complications associated with exclusive breastfeeding!

Caulfield mentions the national Infant Feeding Survey 2010 that we referred to earlier, suggesting that it shows women stop breastfeeding because of a lack of access to support services, misinformation, negative experiences and cultural barriers. She misses out the three main reasons women gave in this survey for stopping breastfeeding: 1. Pain; 2. Latching difficulties; 3. Low milk supply. These are all problems for which there are currently no evidence-based strategies.

She goes on to highlight low breastfeeding rates among young mothers and women who left education before the age of 18. Quite remarkably, she states that low breastfeeding rates in this population result in a ‘cycle of deprivation’ and widening of disparities even further. She seems oblivious to the fact that breastfeeding is a feeding method favoured by more privileged families, and it is likely privilege, not breastfeeding, that leads to better health outcomes. You cannot breastfeed your way out of poverty!

Among other things, Caulfield emphasises a commitment to all maternity services having an ‘accredited evidence-based infant feeding programme by 2024’. This sounds good, but this probably refers to the so-called ‘Baby Friendly Initiative’. Here is a recent Public Health England commissioned review of the effectiveness of this approach. Unimpressive! This review shows no long-term increase in breastfeeding rates, no evidence of improved health outcomes in the UK or a comparable context and potential harmful effects on maternal mental health. Completely absent from both this paper and the Parliamentary ‘debate’ is any consideration as to the safety of the initiative, but concerns have been raised elsewhere, e.g.:

https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjamapediatrics.2016.1529…

https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.acap.2017.11.005…

https://doi.org/10.7759%2Fcureus.18478…

Women get no choice about whether they wish to engage with so-called ‘Baby Friendly’ practices. Information about formula they receive is restricted, including no demonstrations in antenatal classes and no information on public view, whether they like it or not. They get no choice about the option to use a newborn nursery while recovering from birth. And yet this is what passes for a ‘debate’ about breastfeeding support in Parliament?

There is no room to question the dominant narrative here. There is certainly no consideration of the potential for these policies to have unintended adverse consequences, including the very real risk of pouring millions of precious public health resources into breastfeeding support programmes that have yet to demonstrate any return of investment in the form of improved health or educational outcomes. Health inequalities will not be resolved by getting more younger and less economically advantaged women to breastfeed. This is an overbearing, tone deaf policy that focuses entirely on breastfeeding, not on meeting the needs of families, or even the nutritional needs of babies.